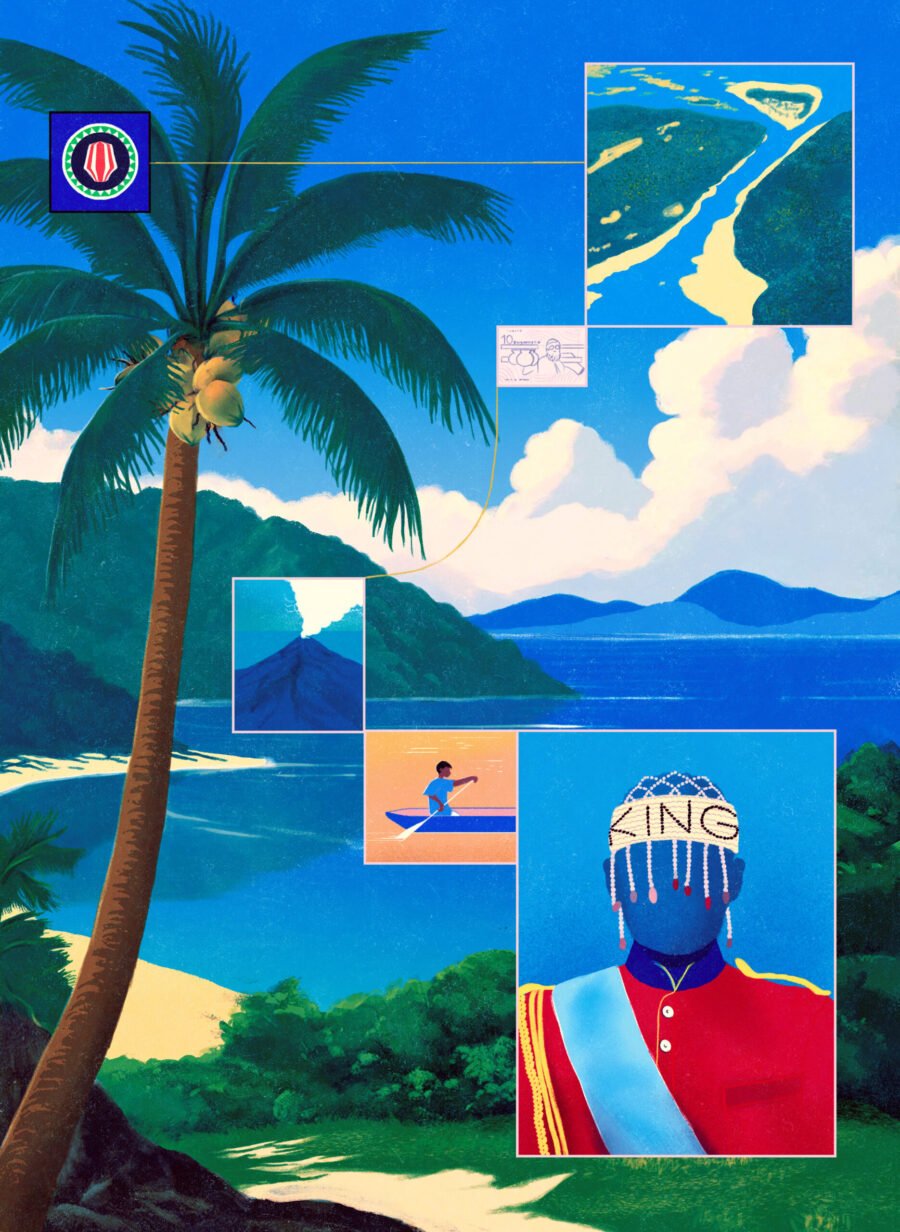

The Island King

Illustrations by Daniel Liévano

Listen to an audio version of this article.

One morning last November, I boarded a plane from Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea, to Buka, the capital of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville. A collection of islands and atolls the size of Puerto Rico, Bougainville is located some six hundred miles east of Moresby, across the Solomon Sea. Its southern shore is just three miles from the politically independent Solomon Islands, and its people share a culture, linguistic links, and dark skin tone with their Solomon neighbors. But thanks mostly to…